In 1739 Bordeaux’s Royal Academy of Sciences announced a competition for the best essay on the physical cause of “Black Skin and hair.” Sixteen essays, written in French and Latin, were ultimately dispatched to Europe’s first great “race contest.” The international cast of authors who participated included naturalists, physicians, theologians, and amateur savants. Some of their essays claimed that Africans had fallen from God’s grace; others that blackness had resulted from a brutal climate; several talked about humoral imbalances; one surgeon who had worked on a New World plantation emphasized the anatomical specificity of Africans. Despite their differences, looming behind these essays is the fact that some four million Africans had been kidnapped and shipped across the Atlantic by the time the contest was announced.

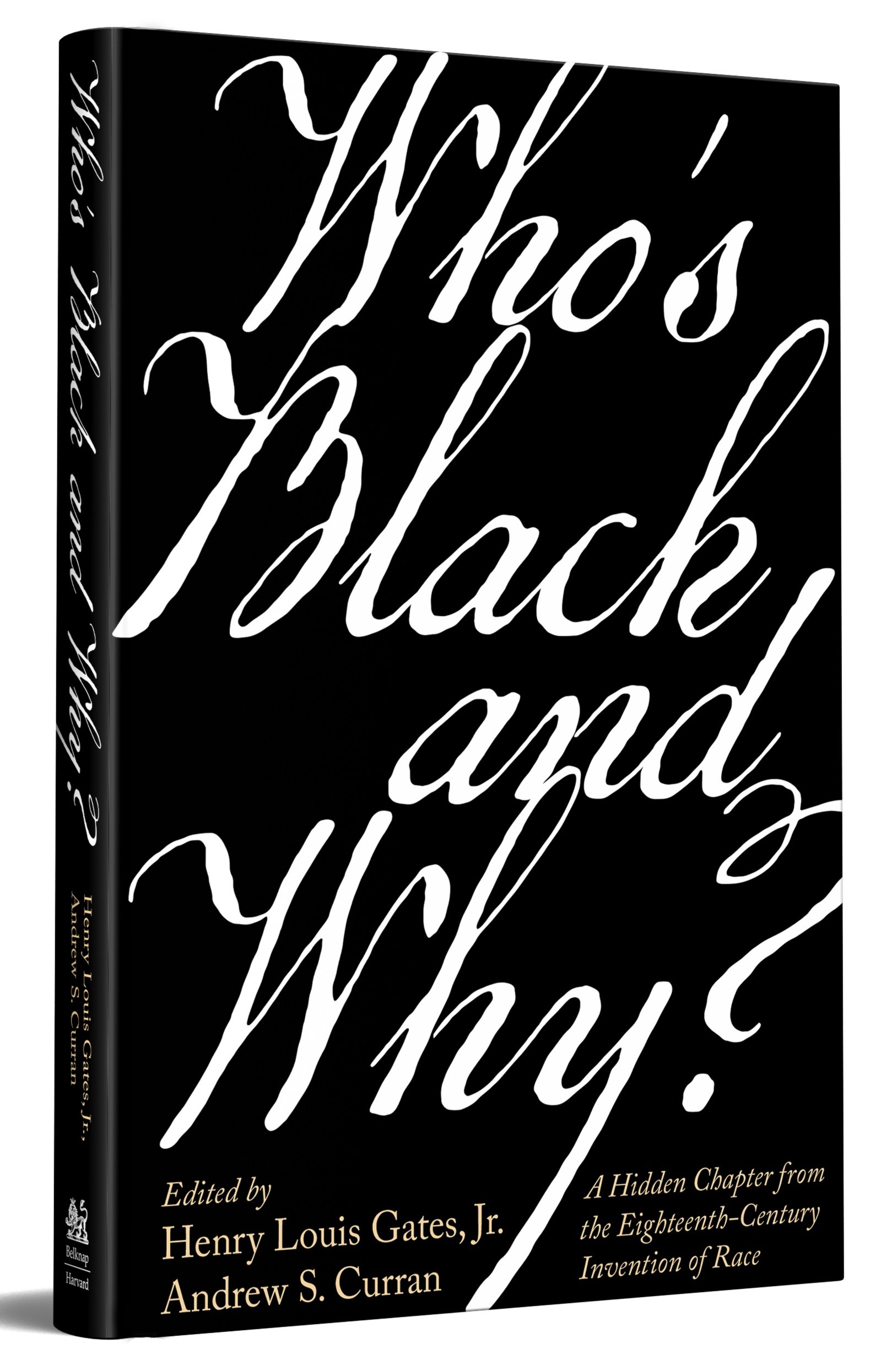

These manuscripts have survived the centuries tucked away in Bordeaux’s municipal library. Brought to life by a team of professional translators, and accompanied by a detailed introduction, timeline, and headnotes by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Andrew Curran, each essay included in this volume not only lays bare the origins of anti-Black racism in the West; it provides an indispensable record of the Enlightenment-era thinking that normalized the sale and enslavement of Black human beings. Visit www.whoisblackandwhy.com.

PRAISE

“An indispensable book for anyone who is interested in the origins of racism. In this essential volume, Gates and Curran reveal how science itself played a major role in the construction of race during the eighteenth century.”

“In 1741 the Royal Academy of Bordeaux (a city of slave-trading wealth) sought the essence of human Blackness: in the climate, in the blood, in the bile, in the semen, in divine providence and the curse of Ham, in the size of the pores, or in ‘tubes’ in the skin. Now, after some 300 years of frustrating searches, definitive answers still elude us. Who’s Black and Why? reveals how prestigious natural scientists once sought physical explanations, in vain, for a social identity that continues to carry enormous significance to this day.”

“The essays translated—and brilliantly contextualized—in this book provide a window into how European thinkers in the eighteenth century struggled with the legacy of religious ideas about human difference as they began to shape a new scientific understanding of race. They give us a fascinating insight into the early stages of the Enlightenment, reminding us that, whatever we owe to this period, we live now in a radically different intellectual world.”

“Eye-opening…A fascinating, if disturbing, window onto the origins of racism. ”

“The eighteenth-century essays published for the first time in Who’s Black and Why? contain a world of ideas—theories, inventions, and fantasies—about what blackness is, and what it means. To read them is to witness European intellectuals, in the age of the Atlantic slave trade, struggling, one after another, to justify atrocity.”

“There is nothing inevitable about modern understandings of race. Gates and Curran have given us unprecedented access to forgotten eighteenth-century conversations that established a moral and intellectual basis for enslaving Black people. This extraordinary book reveals how Europeans learned to think about groups of people as profoundly different from each other simply based on their ancestry. It also provides an important lesson for those who study human variation in our own time. To what extent are we vulnerable to the same intellectual traps?”

“In Who’s Black and Why? Henry Louis Gates and Andrew Curran do the work of archival historians, and to a very available end: making us understand—through documents at times appalling, at times appallingly comic—a subject all too often hived off to abstractions, that is, how we construct a racial group, and how we come to treat as truths what we know to be inventions. An invaluable historical study, with all too many applications today.”